My first AI

Expecting the expected, Part One

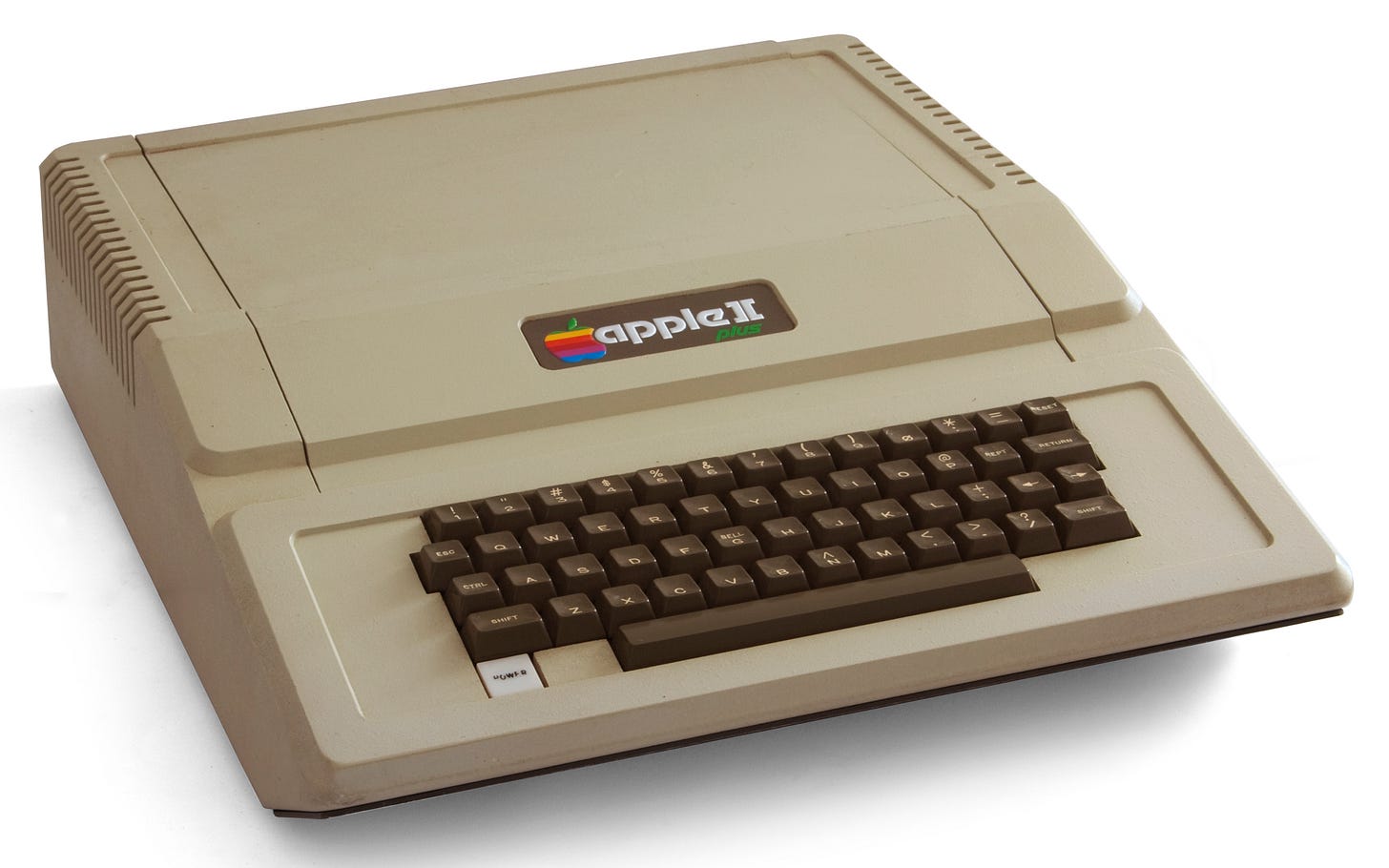

True story! It’s 1985. I am fifteen years old, and I have just spent no more than half an hour writing a jaw-dropping computer program in BASIC on the family Apple II+ “microcomputer” with 48k of RAM.

I run my program, and it greets me with the output below, letters glowing in green dots on a black screen. At each “>” it waits for me to type something and press return. Then it answers me, prints another “>”, and waits again.

Twenty Questions, a computer game

I am thinking of something at random. Can you guess it?

Type a question at each ">" prompt, and I will answer Yes or No.

> Is it alive?

Yes

> Does it live in the water?

No

> Does it fly?

No

> Is it dangerous to people?

Yes

> Is it taller than a person?

No

> Is it smaller than a mouse?

Yes

> Does it bite?

Yes

> Is it poisonous?

No

> Does it have more than six legs?

No

> Is it a parasite?

Yes

> Is it a worm?

No

> Does it spread disease?

Yes

> Is it lice?

YesWould you believe this took no more than a dozen lines of code? And that’s in the BASIC computer language, whose capabilities are truly worthy of the name. Yet, those few lines do everything from processing the text to determining the answer and displaying the output.

“Very nice, honey,” says my mom, underestimating and encouraging at the same time, as only a mom can.

My little program is the only thing running—no extensions, no plugins or servers, no database, no dictionary. The computer is not “connected” to anything but the wall socket for power. It’s 1985. We’ve never heard of the Internet.

How does it work?

Let’s run it again.

Twenty Questions...

> Are you thinking of a historical figure?

Yes

> Is it Abraham Lincoln?

No

> Is it a man?

No

> Is it a woman?

No

> Are you sure you're thinking of a historical figure?

Yes

> But it's not a man or a woman?

No

> So it's not a person?

No

> Is it alive?

Yes

> Is it real?

No

> And you're SURE this is a historical figure?

Yes

> Does "historical figure" include folklore?

Yes

> Aha! Is it an animal from a folk tale?

Yes

> Is it smaller than a dog?

No

> Is it from an American tale?

Yes

> Is it smaller than a grisly bear?

No

> Is it brown?

No

> Is it gray or green or black?

No

> Is it blue?

Yes

> Is it Paul Bunyan's ox, named Babe?

YesWow! If you were wondering whether it just answers randomly, I think we’ve debunked that, but just to make sure, we’ll start the next run by asking the same question several times in a row.

Twenty Questions...

> Is it an animal?

No

> Is it an animal?

No

> Is it an animal?

No

> Is it a vegetable?

Yes

> Is it a vegetable?

Yes

> Is it a vegetable?

YesOkay, same question always yields same answer.

Let’s poke it harder. Remember, this time it’s a vegetable.

> Does it have a long nose?

Yes

> Does it have a short nose?

Yes

> Is it green?

No

> Is it green cabbage?

Yes

> Did I win?

NoNot so impressive. What happened?

Restarting once again:

Twenty Questions...

> Do I have a big nose?

Yes

> Do you like my nose?

Yes

> Do you like your nose?

Yes

> Do you like everyone's nose?

Yes

> Do you just say yes whenever my question ends with "nose"?

Yes

> What about ears?

No

> I don't even have to ask a question.

No

> You have no idea what I type.

Yes

> What is your favorite color?

No

> What is two plus two?

No

> dogs or cats but slowly and sunshine

Yes

> making sense no reason or lunchtime serendipitous adjudicate

YesOkay, time to confess!

The program answers “Yes” whenever the last letter of the user’s text is “E.” It answers “No” for everything else. That’s it.

The rest is all you, your projection onto this canvas of running words, which are mostly yours.

Notice that in our first two sessions above, we ask questions in good faith, interpreting the computer as a clear thinker whose answers mean something. We willingly formulate each question to split the remaining field of possibilities that we perceive within all previous questions and answers—doing all the heavy lifting ourselves—stopping when we identify a clear possible answer.

It had better end in an “E”! Only 19% of English words do, but that is the most common case. If not, we’ll respond to the “No” by troubleshooting and subdividing and relabeling within the tight remaining boundary until we unwittingly supply the necessary “E.” Then we will congratulate ourselves and stop playing. Good thing, because the computer has no idea we’ve won—it can’t tell the critical “Yes” from any other—and will happily continue answering until the twentieth question has passed, at which point it will declare us a loser and exit.

To come up with “lice” above, I had to search the web for small non-flying creatures with no more than six legs that pose a threat to people but are not poisonous. It took a while, but I found one—had it not ended in “E,” I would have kept looking. In 1985, we would have thumbed through the Encyclopedia Brittanica, almost guaranteed to be present in any living room with a microcomputer.

I admit to rigging the second run to land on Paul Bunyan’s ox—on the nineteenth answer, no less. I just wanted to show it handling a greater range of questions, including the nuances of a fictional answer, so I picked my E’s carefully.

This program made the rounds of the home computer hobbyist world in the mid 1980s, gleefully profiled in monthly magazines such as Byte, Creative Computing, and the Computer Recreations column of Scientific American, all of which I received printed on paper in my mailbox at the end of the driveway.

Many a geek secretly chortled to see teachers, parents, and friends pinch themselves at the illusion of a computer arisen to sentience under the spell of BASIC after one period of study hall. When perfectly executed, the con might reach its peak as the bell rang, when the scammer would abruptly shut off the computer to leave for the next class. These computers had no hard drives, so the program would be gone forever, depriving our mark of any chance to poke at it and discover the ruse.

But a skeptical user quickly unmasks this program as a fraud. There’s clearly no one home, and then it’s embarrassing how deep the illusion was.

Mirror, mirror

The same happens any time you interact with symbolic information, though it is usually less crude and much more useful.

Your car’s speedometer is just a needle on a spring. It has no inherent meaning, but you can read its numbers and its label “mph,” and you understand why its human designers put it there and labeled it that way. Knowing all this, you project meaning onto it. That’s a good and useful thing, because its designers likewise projected meaning onto you: that you would sit in the driver’s seat and operate the car for a reason. They didn’t provide gauges for humidity or barometric pressure, because of their expectations about your expectations as a driver of the car.

Even the pixels in a movie, captured and edited to give you a visual experience, are governed by these principles. That is why you say, “I am watching Han Solo fly the Millennium Falcon,” not, “I am watching 2,073,600 pixels change colors in an entertaining manner.” Don’t forget the people who captured and edited the pixels, and the expectations they had—of your expectations. This didn’t come about by accident. Without those people, there is no story and no meaning, even if the pixels are pretty, even if they move in complex ways, even if they resemble things.

I have a whole lot more to say about this sort of thing and its role in meaning and communication and culture, but that is just a taste for now. And yes, it tastes like “AI,” because that’s where we’re headed.

This was Part One of a series. Part Two continues here.

CrowdHealth is a community where you can expect the other members to expect to pay your large medical bills!

Notes

Top 10 end of word letters, Cryptography, University of Notre Dame

https://www3.nd.edu/~busiforc/handouts/cryptography/Letter%20Frequencies.html#endletters

E is the most common last letter in English words, at 19.17%.

To get more yeses, we could accept more last letters, but the “E” always worked fine for the Twenty Questions con. There is something realistic about getting more noes than yeses. I guess questions tend to seek out less than half of the field, for instance the classic animal/vegetable/mineral is a three-way split, so you would expect only 1/3 yeses.

The top four last letters combined would give us an even split:

E 19.17%

S 14.35%

D 09.23%

T 08.64%

= 51.39%

Some other methods more subtle than last-letter:

- Count the letters in the question; answer yes for odd, no for even.

- Same, but answer yes when the count is a multiple of 3, otherwise no.

- Hash the text of the question, a standard way of reducing text to a single number that is consistent but unpredictable; answer based on odd/even or multiple of 3 or whatever.

Parasites - Lice, CDC

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/index.html

Although head lice are harmless, body lice spread diseases, including typhus. They crawl and hop but do not fly.

Apple II Plus, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_II_series#Apple_II_Plus

I credit (blame) Apple for my career in computers and my degree in engineering. Without their “microcomputer” in my home from age nine, I might have ended up in the music industry or editing a publication or doing whatever physics majors do. All the physics majors I know are winging it as computer programmers, maybe because they grew up with a microcomputer in their house.

Microcomputer, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microcomputer

A computer small enough to fit in a single family residence. Finally!

BASIC computer language, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BASIC

The Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, created at Dartmouth in 1963. Go, Dartmouth!

Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica

The 1985 offering was its 15th edition, with 32 volumes, each with the heft of a Harry Potter hardback.